International remittances collapsed by 7% last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of the remittance crisis disproportionately affects developing countries which rely on them far more. How Might Fintech Prevent The Remittance Crisis?

Lockdowns and other virus containment measures led to the closure of sectors which typically employ migrants, such as hospitality or construction, while complicating money transfers between host and home countries. Not only does this collapse surpass the 5% fall in remittances that followed the financial crash in 2009; it is also projected to worsen in 2021. The World Bank estimates that remittances will fall by another 7%, and that outliers from the 2020 collapse, such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, which actually experienced an increase in remittances, will not be so fortunate this time round.

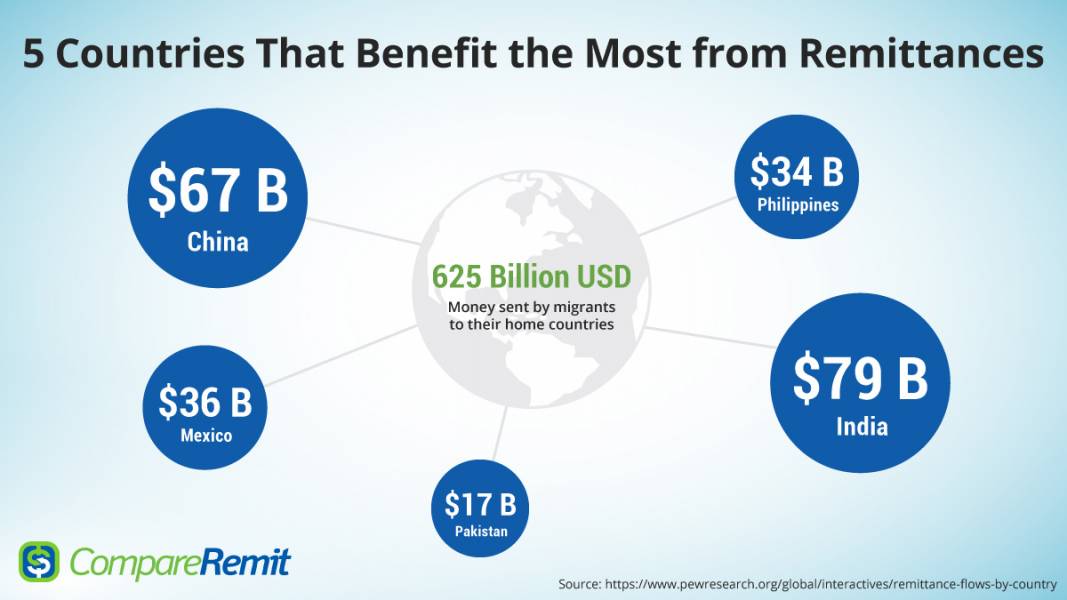

While the impact of the remittance crisis may not be felt so strongly in developed countries, or in export economies such as China (where remittances only account for 2% of total account credit), it disproportionately affects developing countries which rely on them far more. In Bangladesh, remittances represent 29% of total account credit; in Pakistan, that figure is as high as 40%. As of 2018, remittance flows to developing countries reached $350 billion, surpassing foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, and foreign aid as the single most important source of income from abroad. In 2019, the growth rate of remittance flows has been greater than the growth rate of migration. It is estimated that one in nine people worldwide – around 800 million in total – benefits from these flows (ifad.org).

Developing countries face the additional challenge of delayed vaccination programs: 15% of the world’s population, almost exclusively from developed countries, has prebooked half the vaccine supplies for 2021, leaving the other 85% of the world population with limited resources. Confirming this, research by The Economist shows that widespread vaccination coverage will be achieved far sooner in developed countries, and there is a real risk that emerging economies will lose motivation to vaccinate their citizens if the process drags out for several years due to distribution challenges, financing shortages and minimal compensatory social support measures for citizens. A successful vaccine rollout is key to recovering a country’s economy through increased trade, faster turnovers and an optimal working population. That developing countries have to wait longer for this to happen will only exacerbate inequalities between them and the rich.

Although the earlier reopening of the economy in developed countries may at least help increase remittance flows back to developing countries, with the human resources for money transfers becoming more widely available once again, global remittance flows are not expected to recover to pre-COVID levels before 2023, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit. This prediction is itself a best-case scenario, subject to change given the number of variables at play, such as new variants. But where new variants could be a setback, technology can be a lifeline. Replacing the human resources needed for remittance transactions with the equivalent digital resources would allow migrants to send money home without any middlemen and thus facilitate remittance flows by sidestepping additional fees.

Replacing the human resources needed for remittance transactions with the equivalent digital resources would allow migrants to send money home without any middlemen

Indeed, the traditional remittance transaction goes through a commercial bank: the migrant sender pays the remittance to the sending agent using cash, a credit card, a check, or a money (among other options). Costs of a remittance transaction include the fee charged by the sending agent as well as a currency conversion fee for the delivery of local currency to the beneficiary (typically the migrant’s family in his home country), in order to account for unexpected exchange-rate movements. Moreover, remittance agents like banks may earn an additional fee in the form of interest by investing funds from migrants intended as remittances before delivering them to the beneficiary. Interest can rise high in countries where overnight rates can fluctuate upwards, but also poses a significant risk which migrant senders often cannot afford.

Matt Oppenheimer from Remitly, an international money transfer service destined for migrants, argues that the traditional remittance model prevents historically marginalised immigrant communities from finding financial stability in their host country, and that “[e]ven with the rapid growth of financial technology, very few financial apps and services are empowering immigrant communities to easily access, manage, and move their money” (Forbes). Oppenheimer’s mission is twofold: to allow migrants to send money across borders more easily and quickly, and to return “billions of dollars in transfer and service fees that have been taken from immigrant workers and pocketed by antiquated remittance companies”.

Technological innovations in Fintechs such as Remitly or, more famously, Revolut and Monzo (the UK’s fastest growing company in 2020, with £19.7 million in turnover), can disrupt this unsettling power dynamic by giving more autonomy to the sender, all the while encouraging more regulated remittance flows uninterrupted by self-interested third-party investments. However, the challenge to extend financial technology services to migrants remains valid; the question of how to democratise fintech has puzzled and obsessed innovators for years, and remains the biggest hindrance to widespread fintech implementation. Until the quality of the technology is matched in quality by its distribution, fintech services will remain fundamentally exclusive.

Fintechs can disrupt this unsettling power dynamic by giving more autonomy to the sender, all the while encouraging more regulated remittance flows

Individual online transfer services cannot rewrite the rules of international finance on their own. Rather, innovators and incubators need to work hand in hand with policymakers at government level to make this technological revolution institutional and uproot the static and exploitative model currently in place.

William Hosie is a recent graduate from Magdalen College, University of Oxford, with a keen interest in economics, sustainability and Artificial Intelligence. He has gained experience in digital advertising as content marketing assistant at HEC Paris, journalistic writing as prose editor for The Oxford Review of Books, and financial research while interning with Mayer Brown’s Project Finance division in Paris. He is trilingual in English, French and Spanish, bringing an international edge and linguistic finesse to his work. Hardworking and ambitious, he hopes to become part of a pioneering community of innovative thinkers and content creators, spearheading digital transformation across multiple platforms and wide-ranging industries.