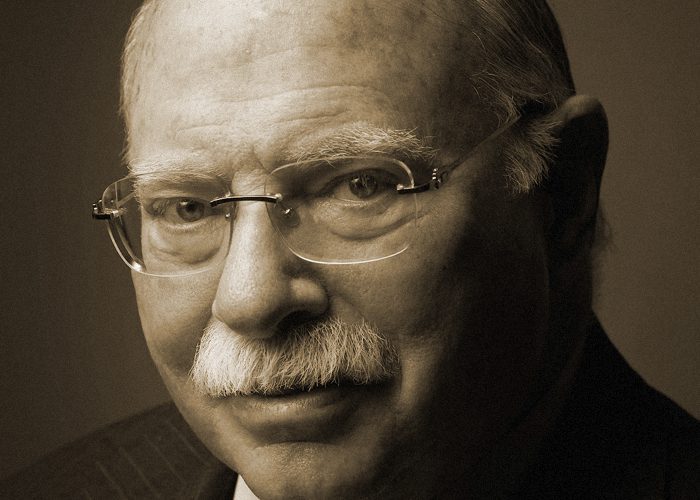

When many of his teenage contemporaries were out smashing windows and slicking their hair back in a vain attempt to look like Elvis Presley, legendary investor Michael Steinhardt was busy reading stock charts and hanging around brokerage offices. This precocious behaviour could well be an analogy for his entire career – one in which he has ignored the crowd, done his homework, and reaped the rewards.

A young man in a hurry

After graduating from high school at the age of 16, Steinhardt motored his way through a three-year degree at the Wharton School of Finance in three years. He was on Wall Street before the ink was dry on his degree certificate, working as an analyst and researcher at Calvin Bullock and Loab Rhoades & Co. By the age of 26, he was already starting his own hedge fund, Steinhardt, Fine, Berkowitz & Co, with two of his brightest contemporaries Howard Berkowitz and Jerrold Fine. With Steinhardt at the helm, the firm delivered consistent success by using macro strategies to trade securities, and by 1979, he was in sole control of the company – which was now called Steinhardt Partners.

Steinhardt is a key figure in the evolution of the hedge fund industry, presiding over one of the most consistently successful fund management firms between the halcion days of the industry in the late 1960s and the boom years of the 1990s. From 1967 to 1995 his pioneering hedge fund returned an average of 24.5% annually to its investors, and this was after a 20% performance fee. Naturally, he did very well out of the whole endeavour, and by 1993 he was among the 400 richest people in the world with an estimated worth of $300 million.

A pessimistic approach to profiteering

As an investor, Steinhardt thought like a long-term trader, but used these insights to make short term strategic trades. Most of his trades were directional in nature, drawing on an eclectic range of securities based upon their exposure to wider trends rather than their position within a certain sector, with a team of analysts on hand to do the necessary due diligence on each stock.

At the outset, Steinhardt’s hedge fund was exactly that – a fund that was solely focused on hedging strategies for its returns. Speaking of his intense fascination with betting on falling prices, he had the following to say:

I really shorted a lot. I liked to short, says Steinhardt. I felt far more gratification from making money on the short side than from the long side, which is a very dangerous thing, because the short side is so tough.

This perverse joy in seeing things fail was to become a prize asset as the stock market nosedived around the oil crisis of 1973-74. With the average mutual fund plummeting in value, the consistent performance of Steinhardt’s pessimism-friendly hedge fund started to turn heads among the investment community, and soon he had money piling in to his hedge fund left, right, and centre. His passion for preserving wealth at all cost became his calling card, and big money was buying into it.

The worst – and best – boss on Wall Street

For me, running hedge funds was an art. It was something that I thought I did exceptionally well, and most of the world did not. But they didnt care the way I did, says Steinhardt. I got depressed if I was having a bad day, a bad week, a bad year.

Most of the top traders on Wall Street have reputations for being horrible bosses, and Steinhardt is no exception. Perhaps the kind of obsessional, perfectionist behaviour that can bring success in the markets isn’t always compatible with the wider goals of people management. In most working environments, a good boss is level-headed and even-handed, but with Wall Street being an environment that fosters aggression, ruthlessness, passion, and perfectionism, it’s perhaps inevitable that you won’t find too many of them there. And, by his own admission, Steinhardt definitely wasn’t one of them:

When I did well, I was happy, Steinhardt says. When I did poorly, I was intolerant and difficult and had a bad temper.

And that’s putting it mildly. Steinhardt was notoriously the worst bosses Wall Street has ever seen, with his employees using phrases such as random violence, battered children, mental abuse and rage disorder to describe their experience of working under him. But, regardless of how good or bad he was to work for, he got results – consistently some of the best results on Wall Street, year after year for the vast majority of his career.

They always say to “go out on a high”, but most hedge fund managers tend to exit the business after a remarkable run of success has been cut short by a heavily-overleveraged dose of bad luck. Not so with Steinhard, who quit the hedge fund business with both his fortune and reputation intact after his fund gained 21% in its last year, although the exit had been prompted by a tough loss in the previous year, in which his fund lost 30%.

Straight from the horse’s mouth

As one of the most quotable – and widely quoted – investors in the history of Wall Street, Steinhardt’s philosophy is best expressed in his own words:

“Somehow, in a business [securities trading] so ephemeral, the notion of going home each day, for as many days as possible, having made a profit that’s what was so satisfying to me.”

“One dollar invested with me in 1967 would have been worth $481 on the day I closed the firm in 1995, versus $19 if it had been invested in a Standard & Poor’s index fund.”

“I do an enormous amount of trading, not necessarily just for profit, but also because it opens up other opportunities. I get a chance to smell a lot of things. Trading is a catalyst.”

“I always used fundamentals. But the fact is that often, the time frame of my investments was short-term.”

In 2004, Steinhardt made a speech which was later immortalised by Charles Kirk, publisher of The Kirk Report, who gleaned these “rules of investing” from this address:

- Make all your mistakes early in life. The more tough lessons early on, the fewer errors you make later.

- Always make your living doing something you enjoy.

- Be intellectually competitive. The key to research is to assimilate as much data aspossible in order to be to the first to sense a major change.

- Make good decisions even with incomplete information. You will never have all the information you need. What matters is what you do with the information you have.

- Always trust your intuition, which resembles a hidden supercomputer in the mind. It can help you do the right thing at the right time if you give it a chance.

- Don’t make small investments. If you’re going to put money at risk, make sure the reward is high enough to justify the time and effort you put into the investment decision.

Bucking the trend of secretive, publicity-shy Wall Street investors, Steinhard never shied from the limelight, and was all too eager to share his investing wisdom with the public, giving speeches and interviews aplenty in his later years. Perhaps the greatest distillation of his investing philosophy can be found in his autobiography, “No Bull: My Life In And Out Of Markets” which was published in 2001.

I am a writer based in London, specialising in finance, trading, investment, and forex. Aside from the articles and content I write for IntelligentHQ, I also write for euroinvestor.com, and I have also written educational trading and investment guides for various websites including tradingquarter.com. Before specialising in finance, I worked as a writer for various digital marketing firms, specialising in online SEO-friendly content. I grew up in Aberdeen, Scotland, and I have an MA in English Literature from the University of Glasgow and I am a lead musician in a band. You can find me on twitter @pmilne100.