Back in the early days of his Wall Street career, Paul Tudor Jones II’s colleagues often spoke of his ability to shoot the lights out by scoring massive profits on big market swings. These days, however, people are more likely to talk about the Christmas light show at his 13,000 square foot mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, than they are about his ‘light shooting’ ability.

Unlike many traders, who start out as workaholics and stay that way until the bitter end, Jones has been only too happy to take his foot off the gas in recent years and enjoy spending – and re-distributing – the vast amount of wealth he has accumulated.

Originally from Memphis, Jones started out as a commodities trader in New Orleans, mainly trading cotton, before making a move to Wall Street in the 1980s. Like many legends of the hedge fund industry, he made his name by betting on a big downturn in the US stock market in 1987, anticipating the events of Black Monday. Making massive returns of 129% that year certainly put him and his hedge fund on the map, and he repeated the trick in 1990 when the market plunge in Japan saw him rake in 87.4% profits. and again with the bursting of the tech bubble in 2001-2, when he returned 48.1% betting against technology stocks.

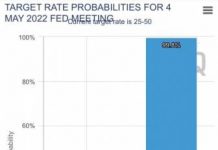

Since then, his results have been somewhat less spectacular, and there are several reasons why this might be. One has been a deliberate effort on Jones’ part to trade more conservatively and preserve wealth rather than go all-in on big risky moves. Another is that the moves by central banks to keep interest rates near zero have reduced the amount of opportunities for macro traders looking for big interest-rate and currency moves. Also, the competition in the hedge fund industry has multiplied by several times over this period, making it more difficult to spot these big opportunities before someone else does.

Although Jones’ $10.3bn flagship fund, Tudor BVI Global, can still claim long-term annual returns of close to 19.5%, he hasn’t hit that level in 11 years. In fact, between 2010 and 2012 he averaged just 5% annually – his worst three year stretch ever – although he did return 14.3% in 2013 with some winning bets against Japan’s stock market and the yen.

To compound his woes, two of his smaller funds – managed by other traders – have been reporting losses since 2011, with one of them, Tudor Tensor, which boasted a 35% profit in 2008, shrunk to $700 million from $1.4 billion in 2010.

But in spite of his mediocre recent trading performances, Jones remains a Wall Street legend, having made an estimated $100 million in the United States market crash of 1987. Later, he cemented his fame (and wider goodwill) by co-founding the Robin Hood Foundation, dedicated to fighting poverty in New York City, to which he personally donated $1.25 billion.

Trading style

Rather than focusing on individual companies or sectors, Jones could be described as a macro trader in the vein of George Soros, making big bets on moves in interest rates and currencies that are based on economic changes in different countries. Opportunities to do this have been scarce since the financial crisis, with central banks keeping rates low in an effort to revive the global economy.

However, it could be that large-scale successes with this type of strategy are, by their very nature, impossible to repeat on a consistent basis. Traders such as Jones and John Paulson made their names with huge gains from major market events – Paulson made a lot of money from the bursting of the subprime mortgage bubble in 2007 – but often find it hard to avoid disappointing investors further down the line, when these opportunities just aren’t available.

Jones and Paulson aren’t alone in feeling the pinch, as other top macro traders have had a hard time in recent years. For example, Bridgewater Associates $80 billion Pure Alpha fund returned 5.3% percent last year, well below its 13.5% annualised return since 1991, while Brevan Howard Asset Managements $28 billion Master Fund returned just 2.6%.

Jones’ trading style is one that requires a lot of concentration, stamina and quick thinking, and age may be a factor in his declining performance. He has compensated for this, to a certain extent, by hiring younger traders to help trade his funds, but it seems that few are possessed of his market genius. Across his four Tudor funds, totalling $13.6 billion, Jones is only responsible for 20% of the positions, with 35 other portfolio managers making up the rest.

By contrast, in his 80s and 90s heyday, Jones was almost solely responsible for all the positions taken up by his hedge funds. The type of money he has been investing has changed, too – back in the 80s, he was mainly investing on behalf of high-net-worth individuals, but over time he has accepted much larger sums from pension funds and other institutional investors. This has forced him to invest more conservatively, and has prevented him from taking the kind of big risks that made his name in the first place.

And unlike on previous occasions where he made massive profits from market plunges, Jones was caught napping during the financial crisis of 2008, and while he wasn’t the worst affected by a long way, he did still lose 4.9% in what has been his only down year to date. This prompted him to restructure his main fund to boost liquidity, and cut risk by reducing the loss limits for individual traders, resulting in a split with his long-time partner James Palotta.

After posting poor returns between 2010 and 2012, Jones cut the management fee for a new share class of Tudor BVI from 4% to 2.75% and boosted his performance fee from 23% to 27%, in an effort to address concerns about poor returns. However, even the lower management fee was enough to bring in $283 million on the main fund alone.

Changing priorities

Above all else, the lacklustre recent performance of Jones’ hedge funds seems to stem from taking his eye off the ball. With a reported net worth of $3.7 billion, Mr. Jones ranks No. 130 on the Forbes 400, and lately seems to have been putting more effort into spending his money on good causes than making bumper profits for his investors.

As well as his $1.25 billion donation to his Robin Hood Foundation, Mr. Jones is a keen environmentalist, and has served as chairman of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Everglades Foundation, two conservation groups. In addition, he owns a $30 million hunting and fishing lodge in Maryland, another home in the Florida Keys, and a 350,000-acre eco-reserve in Tanzania, where he co-owns four high-end lodges that he leases out.

Like most hedge fund billionaires, he has been a generous donor to his alma mater, and donated $44 million for a sports and concert arena there in 2012, as well as $12 million for a meditation, yoga, and mindfulness training centre. He was involved in an unsuccessful effort to unseat the college’s president later that year.

But while he may have gone off the boil somewhat as a trader, given his increasingly conservative attitude towards investing and his enthusiasm for delegating responsibility to younger traders, he remains a true Wall Street legend, and his philanthropic efforts have won him acclaim from a much wider section of society.

I am a writer based in London, specialising in finance, trading, investment, and forex. Aside from the articles and content I write for IntelligentHQ, I also write for euroinvestor.com, and I have also written educational trading and investment guides for various websites including tradingquarter.com. Before specialising in finance, I worked as a writer for various digital marketing firms, specialising in online SEO-friendly content. I grew up in Aberdeen, Scotland, and I have an MA in English Literature from the University of Glasgow and I am a lead musician in a band. You can find me on twitter @pmilne100.