This article has been written with the help of several sources including Wikipedia, the Financial Times, the Handbook of Hedge Funds by Francois-Serge Lhabitant, the Managed Funds Association and Interviews with Ram Ananth from Nomura.

The article and the analysis it contains are also based on the author’s own experience of the Hedge Fund Industry as he worked as a quantitative analyst at Cambridge Place Investment Management, a leading Hedge Fund in fixed income, structured credit and asset-backed securities investing

In this three-series article, after giving a brief background of the Hedge Fund industry, we shall shed light on the impact of regulatory changes on the industry since the onset of the financial crisis both in Europe and the US, and the corresponding operational challenges faced by managers.

Hedge funds are investment vehicles that pool capital from several types of investors (institutional like pension funds, endowments but also private investors) to invest in securities using different types of strategies. Hedge Funds are generally distinct from mutual funds in the sense that they are not restricted to the same diversification rules and leverage constraints. They also differ from private equity funds as they invest in relatively liquid assets.

In Europe, assets under management held in Hedge Funds currently total 549 billion USD for a total of 2.4 tn$ for the industry worldwide. Some hedge funds have several billion dollars of assets under management (AUM) and overall, hedge funds represent 1.15% of the total funds and assets held by financial institutions. In Europe, the ESRB (European Systemic Risk Board) has a mission to implement macro prudential oversight of the financial system within the Union as non-regulation of the Hedge Fund industry has proven a large systemic risk for the financial system as a whole.

Hedge Fund investment strategies aim to achieve a positive return on investment regardless of markets directionality (“absolute return” or “alpha”) and magnify those returns through the use of leverage.

Historically, hedge funds could not be proposed and sold to the general public or retail investors. Therefore hedge funds were not under the same regulatory constraints and scrutiny that govern other funds like mutual funds and had a wider range of choice in terms of investment structuring, strategies and structures that they could implement. However, with the financial crisis of 2007-2008, regulations passed in the United States (Dodd-Frank) and Europe (AIFMD) to increase regulatory oversight of hedge funds, eliminate certain regulatory gaps in order to reduce global systemic risk.

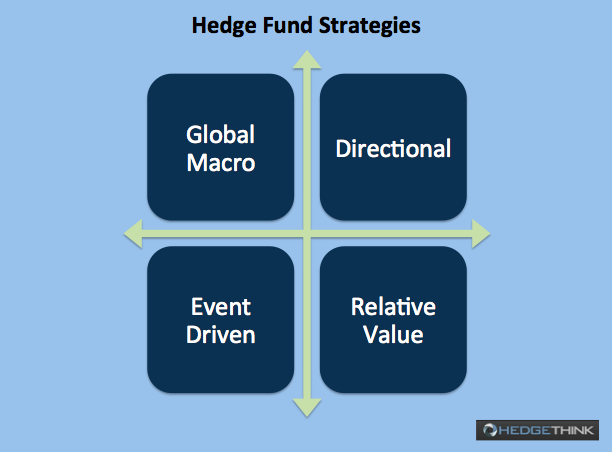

Hedge Fund strategies are generally classified among four major categories: global macro, directional, event-driven and relative value (arbitrage) that correspond to different risk-return characteristics.

This list is by no means exhaustive and hedge funds can approach investments through a wide range of strategies and techniques. For instance, quantitative hedge funds use advanced computational and algorithmic techniques to identify profitable investment strategies. A fund may deploy a single strategy or multiple strategies for flexibility, risk management and diversification. The offering memorandum of a Hedge Fund will describe key aspects of the fund, including its investment strategy and leverage limit.

The term “Hedge” often refers to the hedging strategy that is being used by portfolio managers to cover their exposure and limit their risk, thus the name “Hedge Fund”. However, this is not restrictive in the sense that a Hedge Fund does not necessarily use hedging and may simply follow a long-only, long-term buy-and-hold investment approach through top-down or bottom-up investment analysis.

In fact, a Hedge Fund may be structured as an umbrella to different but related investment strategies with different return targets and risk-return profiles. For instance, a structured credit leverage fund could have different target returns like LIBOR + 500 bps or LIBOR + 1000 bps or LIBOR + 1500 bps. A higher target return will correspond to a higher level of risk or use of leverage or both. In the context of measuring returns of a hedge fund, the Sharpe ratio (risk-adjusted measure of return) is a key performance indicator that measures the risk adjusted return per unit of risk. Mathematically, it will be expressed by the real return minus the risk-free rate (or any other benchmark) divided by the standard deviation (measure of volatility). This is in essence the bottom line that measures “alpha”.

It is critical to understand the Hedge Fund industry in terms of systems, models, reporting structures and processes points of view. By processes, we mean both business and operational processes. This is all the more important as Hedge Funds need to develop investment and trading strategies that can sustain the test of time. Essentially, hedge fund managers will need to revisit their strategy on an ongoing basis depending on the evolutions in terms of technology, regulation and the economic environment, both at micro and macro levels.

What allows a Hedge Fund to gain competitive advantage in the market place is its ability to seek alpha while managing its risk effectively and proactively. And for this, a Hedge Fund needs to rely on lean and efficient operations: it needs to have the right technology and architecture to be able to analyze information very quickly.

In this paradigm, lean technology will be one of the drivers of a Hedge Fund competitive advantage. A Hedge Fund will need the right type of technology to gain superior ability to organize and structure data quickly and make fast and efficient computations to support the decision making process. The Hedge Fund business is all about interpreting signals and using that interpretation to implement the right asset allocation strategy. For this, a Hedge Fund will need the right integrated framework for optimal decision making.

Jean Lehmann is an independent consultant and editor and business ambassador to Hedge Think. He currently lectures at INSEEC on Banking Management and the Hedge Fund industry, and is a member of Keiretsu forum, a global investment community of accredited private equity angel investors, venture capitalists and corporate/institutional investors. Jean has extensive consulting experience for leading such projects as the market entry strategies in the Brazilian market of several mid-size to large European financial institutions. Jean has considerable knowledge of the Hedge Fund and Asset Management industry, for having developed as a quantitative analyst some of the most sophisticated financial models in the structured finance product market for a leading US Hedge Fund and a German investment bank. He also has particular expertise in the field of Network Security and Cryptography. As a research staff member at IBM Zurich, he developed innovative algorithms for anonymous communication systems. He was also in charge of Brazilian security consulting services for Gemalto and recently completed a CyberSecurity consulting study for a European airline company. Jean holds a MSc. in computer science and telecommunication engineering with an emphasis on network security and cryptography from ENST Br/EPFL, a DEA in financial mathematics from HEC School of Management, and an MBA from INSEAD