In April 2014, hedge fund legend Paul Tudor Jones – who we profiled last week in our article ‘Paul Tudor Jones II – Shooting The Lights Out‘ – shocked the investment world with the news that he was shutting down one of the funds that bears his name, the Tudor Tensor Fund.

This prompted much kneejerk reaction – particularly on Twitter – on the topic of whether alternative investments were still worth the risk. After all, if a legend like Paul Tudor Jones can’t make money with his futures fund, what hope is there for the rest of them in the long run?

It is true to say that, as a whole, the alternative investment industry has had a tough time in the post-financial crisis years. For example, most hedge funds – with a few notable exceptions – lost money in 2008, and many more had a down year in 2011. And while the industry as a whole has bounced back from these lows to a certain extent, returns are on the whole a long way off their pre-crisis peaks.

Hedge funds under pressure

There are several reasons for this. One is the hugely increased regulatory burden in the wake of regulations such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the US, which have both placed greater restrictions on the activities of money managers working in the alternative investment sphere, and increased the costs of running an alternative investment fund significantly. At the same time, market conditions have not favoured many of the strategies pursued by funds such as Tudor Tensor.

Also, an influx of money from institutional investors such as pension funds into an industry traditionally dominated by wealthy individual investors has increased the administrative burden and diluted the returns from larger funds, with many of them handing money back to investors in an effort to stay agile and produce better percentage returns.

There is an argument to made around the issue of survivorship bias, because the indices composed of hedge fund returns do not include funds that have shut down, creating a false impression of the profitability of hedge fund investments. Even with this in mind though, the figures for 2013 were not good, with only a handful of hedge funds outperforming the S&P 500, and the industry as a whole lagging far behind the stock market.

But before we start writing an obituary for the alternative investment industry, it might be worth taking a look at what a hedge fund failure actually looks like. How bad does the performance of a fund have to be before it is shut down?

What a failed hedge fund looks like

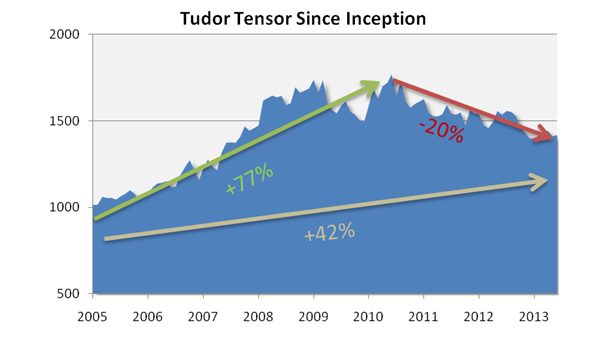

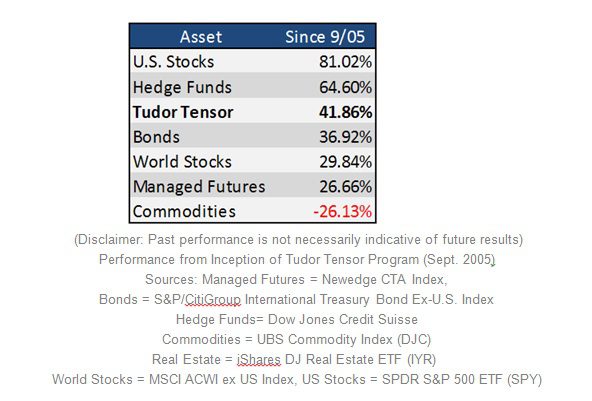

In the case of Tudor Tensor, it’s not actually that bad at all. From its inception in 2005 to 2010, the fund posted returns of 77%, but in the last three years of its existence it posted losses of 20%. Taken as a whole, it’s still a net profit of 42% – not bad for an eight and a half-year investment during one of the most difficult trading periods since the Great Depression.

In comparison with the benchmark for managed futures and the markets they track, the Tudor Tensor fund didn’t perform that badly at all – and it also outperformed investments in bonds and world stocks.

While the closure of the fund could be taken as a sign that this strategy simply doesn’t work any more, or that Paul Tudor Jones no longer had what it takes to succeed with managed futures, the truth behind it lies in the business side of hedge funds. When funds make losses, investors pull out and put their money into better-performing programs in order to maximise returns.

As a result, the amount of assets under management at the Tensor Fund went down from over $1 billion to just $120 million over the course of its three down years, and this is why the fund was forced to close. It had little to do with the long-term prospects for the investment model – of which this three-year downturn surely marked a temporary low in the long-term picture – the skill of the manager, or the expertise of the team. It is simply a symptom of the pattern of investors buying in at the top of a cycle and getting out at the bottom.

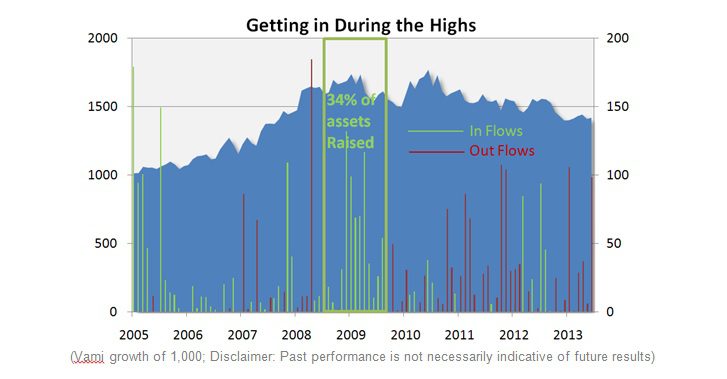

This is demonstrated by the following chart, which shows the Tensor equity curve overlaid with the assets raised (with green denoting money flowing in, and red showing money going out). This is calculated as the growth in AUM minus the performance multiplied by the previous months AUM to provide an estimate of how much of the AUM growth came as a result of performance rather than asset raising. As you can see, the biggest concentration of money (more than 34% of all the money raised) came in just as equity peaked and was poised to begin a draw-down period that is wholly in keeping with the typical performance of this type of strategy over the business cycle.

After four years of good performance, $700 million in assets came flooding into the fund at precisely the wrong time. This pattern of fund flows is one that can be seen time and again in the investment industry, from mutual funds to alternative investments, and only goes to show that even a big name hedge fund manager like Paul Tudor Jones isn’t immune to the effects of performance-chasing.

But no matter how well Tudor and his team might have thought that the program would perform over the longer term, the simple fact is that a $100 million fund isn’t worth keeping on for a multi-billion dollar fund management shop like Tudor in terms of time, effort, and administrative expenditure. In situations such as these, the standard practice is for hedge fund management firms to shut down funds when they fall into this category and move onto other projects that stand a better chance of succeeding in the near-to-medium term.

I am a writer based in London, specialising in finance, trading, investment, and forex. Aside from the articles and content I write for IntelligentHQ, I also write for euroinvestor.com, and I have also written educational trading and investment guides for various websites including tradingquarter.com. Before specialising in finance, I worked as a writer for various digital marketing firms, specialising in online SEO-friendly content. I grew up in Aberdeen, Scotland, and I have an MA in English Literature from the University of Glasgow and I am a lead musician in a band. You can find me on twitter @pmilne100.